ASEAN Origins

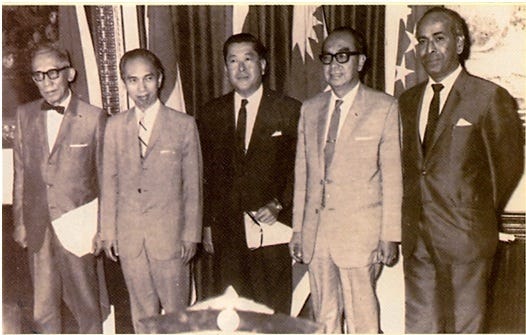

On 8 August 1967, five leaders – the Foreign Ministers of Indonesia, Malaysia, Philippines, Singapore and Thailand – signed the document forming the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The ASEAN Journey

By Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN)

On 8 August 1967, five leaders – the Foreign Ministers of Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines, Singapore and Thailand – sat down together in the main hall of the Department of Foreign Affairs building in Bangkok, Thailand and signed the document forming the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN).

The five Foreign Ministers who signed it – Adam Malik of Indonesia, Narciso R. Ramos of the Philippines, Tun Abdul Razak of Malaysia, S. Rajaratnam of Singapore, and Thanat Khoman of Thailand – would be hailed as the founding fathers of the inter-governmental organization in the developing nations in the regions today. And the document that they signed would be known as the ASEAN Declaration.

It was a short, simply-worded document containing just five articles. It declared the establishment of an Association for Regional Cooperation among the Countries of Southeast Asia to be known as the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) and spelled out the aims and purposes of that Association. These aims and purposes were about economic, social, cultural, technical, educational cooperation and in the promotion of regional peace and stability through abiding respect for justice and the rule of law and adherence to the principles of the United Nations Charter. It stipulated that the Association would be open for participation by all States in the Southeast Asian region subscribing to its aims, principles and purposes.

It proclaimed ASEAN as representing the collective will of the nations of Southeast Asia to bind themselves together in friendship and cooperation and, through joint efforts and sacrifices, secure for their peoples and for posterity the blessings of peace, freedom and prosperity.

It was while Thailand was brokering reconciliation among Indonesia, the Philippines and Malaysia over certain disputes that it dawned on the four countries that the moment for regional cooperation had come or the future of the region would remain uncertain.

Recalls one of the two surviving protagonists of that historic process, Thanat Khoman of Thailand:

“At the banquet marking the reconciliation between the three disputants, I broached the idea of forming another organization for regional cooperation with Adam Malik. Malik agreed without hesitation but asked for time to talk with his government and also to normalise relations with Malaysia now that the confrontation was over.”

“Meanwhile, the Thai Foreign Office prepared a draft charter of the new institution. Within a few months, everything was ready. I therefore invited the two former members of the Association for Southeast Asia (ASA), Malaysia and the Philippines, and Indonesia, a key member, to a meeting in Bangkok. In addition, Singapore sent S. Rajaratnam, then Foreign Minister, to see me about joining the new set-up. Although the new organization was planned to comprise only the ASA members plus Indonesia, Singapore’s request was favorably considered.”

In early August 1967, the five Foreign Ministers spent four days in the relative isolation of a beach resort in Bang Saen, a coastal town less than a hundred kilometres southeast of Bangkok. There they negotiated over that document in a decidedly informal manner which they would later delight in describing as “sports-shirt diplomacy.” Yet it was by no means an easy process: each man brought into the deliberations a historical and political perspective that had no resemblance to that of any of the others. But with goodwill and good humor, as often as they huddled at the negotiating table, they finessed their way through their differences as they lined up their shots on the golf course and traded wisecracks on one another’s game, a style of deliberation which would eventually become the ASEAN ministerial tradition.

Read more here.

ASEAN - Brunei Relations

Source: Ministry of Foreign Affair Brunei Darussalam

Brunei Darussalam joined ASEAN as its sixth member soon after the resumption of her full independence in January 1984. Present at the admission ceremony at the ASEAN Secretariat in Jakarta, Indonesia was His Royal Highness Prince Mohamed Bolkiah, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Brunei Darussalam. Since then, ASEAN has become the cornerstone of Brunei Darussalam's foreign policies. Through ASEAN, Brunei Darussalam participates in various other regional mechanisms including the ASEAN Regional Forum, ASEAN Plus Three and East Asia Summit.

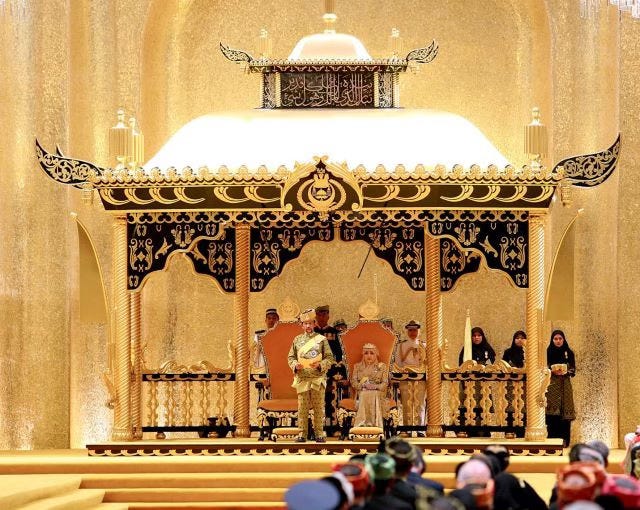

His Majesty the Sultan and Yang Di-Pertuan of Brunei Darussalam together with other ASEAN leaders signed the ASEAN Charter on 20 November 2007 in Singapore. Brunei Darussalam was the second Member State after Singapore to ratify the Charter on 31 January 2008.

Brunei Darussalam nationals who have served in the ASEAN secretariat included Dato Roderick Yong, ASEAN Secretary-General (1986 - 1989); Dato Haji Mahadi Wasli, Deputy Secretary-General (1994 - 1997); and Pengiran Dato Mashor Pg. Ahmad, Deputy Secretary-General (2003 - 2005); and currently Dato Lim Jock Hoi, ASEAN Secretary-General (January 2018 - December 2022).

Read more here.

Brunei Darussalam

Early History

Brunei’s full name is Negara Brunei Darussalam (The Country of Brunei, Abode of Peace) The pre-Islamic history of Brunei is unclear, but archaeological evidence shows the country to have been trading with the Asian mainland as early as CE 518. Islam became predominant during the 14th century and the Brunei Sultanate rose to prominence in the 15th and 16th centuries, when it controlled coastal areas of North-West Borneo, parts of Kalimantan and the Philippines. The Dutch, Portuguese and Spanish began arriving after the 16th century. Brunei lost outlying possessions to the Spanish and the Dutch and its power gradually declined as the British and Dutch colonial empires expanded.

The Sultanate of Brunei's influence peaked between the 15th and 17th centuries when its control extended over coastal areas of northwest Borneo and the southern Philippines. Brunei subsequently entered a period of decline brought on by internal strife over royal succession, colonial expansion of European powers, and piracy.

In 1888, Brunei became a British protectorate; independence was achieved in 1984.

The same family has ruled Brunei for over six centuries. Brunei benefits from extensive petroleum and natural gas fields, the source of one of the highest per capita GDPs in Asia.

In the 19th century the Sultan of Brunei sought British support in defending the coast against Dayak pirates, and ennobled James Brooke, a British adventurer, as Rajah of Sarawak in 1839. The British proceeded to annex the island of Labuan in 1846. North Borneo became a British protected state in 1888 and Brunei voluntarily accepted the status of a British protected state under the Sultan, with Britain having charge of its foreign relations. The loss of Limbang district to Sarawak in 1890 split Brunei into two and remains an obstacle to good relations with Malaysia to this day.

In 1906 a treaty was signed between Britain and Brunei making Brunei a full protectorate. The treaty assured the succession of the ruling dynasty, with the arrangement that a British resident would advise the Sultan on all matters except those concerning local customs and religion.

In 1929 large resources of oil were discovered in Seria; these and subsequent discoveries made Brunei a wealthy country. A written constitution was introduced, giving Brunei internal self- rule and allowing for a legislative council. The residency agreement of 1906 was revoked, transferring the resident’s power to the Sultan and appointed officials below him. Sultan Omar Ali Saifuddien promulgated the nation’s new Constitution on September 29, 1959.

During 1962 there were sporadic and unsuccessful attempts at rebellion, instigated by the North Borneo Liberation Army. These were put down with the help of British Gurkha units flown in from Singapore and the Sultan declared a state of emergency. This has been renewed every two years since.

In the 1960s, Brunei considered merging with the Federation of Malaysia, which at the time included the provinces of the Malaysian peninsula, Sabah, Sarawak and Singapore.

The idea was opposed by the Brunei People’s Party, which at that time held 16 seats in the 33-member legislative council, and which proposed instead the creation of a state comprising Northern Borneo, Sarawak and Sabah. The Sultan finally decided against joining the Federation.

In 1971, under an agreement with the UK, Brunei ceased to be a British protected state. The constitution was amended to give the Sultan full control over all internal matters, the UK retaining responsibility for defence and foreign affairs.

Brunei became a fully independent sovereign state on 1 January 1984.

Ancient History

There is archaeological evidence that early modern humans were present in Borneo 40,000 years ago. These early settlers were later replaced by successive waves of Austronesian migrants, whose descendants form the many ethnic and cultural groups living in Borneo today, alongside more recent immigrants from China, Indonesia, the Philippines and India.

There is archeological and historical evidence that indicates that Brunei was inhabited at least as early as the A.D. 6th century. Chinese historical records from this period use he name “Poli” or “Puni” to describe ancient Brunei. According to Chinese sources Islam had arrived in Brunei by 1371 and the people at that time used an Arabic-like script called “jawi”.

Early Borneo kingdoms were under the cultural, economic and political influence of larger Hindu and Buddhist kingdoms in the Indonesian archipelago. There is evidence of early trade with India and China dating as far back as the 6th century, with a rich trade in camphor, spices, precious woods and exotic jungle products in the area that is now modern-day Brunei. Before the region embraced Islam, Brunei was within the boundaries of the Sumatran Srivijaya empire, then the ―Majapahit empire of Java.

According to Royal Ark, Excavations unearthed near the capital suggest that the Chinese may have controlled, or at least traded in the area as early as 835 AD. Camphor and pepper seem to have been prized objects of trade. Brunei hard camphor had a wholesale value equivalent to its own weight in silver. The kingdom was undoubtedly a very wealthy and cultured one. Ming dynasty accounts give detailed information about visits and tribute missions by rulers of P'o-ni during the late fourteenth and early fifteenth century. Their names and titles suggest either Hindu or Buddhist influence, not Islamic. The texts confirm that the state was tributary to the Hindu Javanese Majapahit Empire but sought and received Chinese protection in 1408.