Fitch and Chips

UPDATE: US Stripped of AAA Rating by Fitch as Budget Deficits Swell

Downgrade reflects expected fiscal deterioration, Fitch says US Treasury futures push higher in early Asia trading. The US was stripped of its top-tier sovereign credit grade by Fitch Ratings, which criticised the country’s ballooning fiscal deficits and an “erosion of governance” that’s led to repeated debt limit clashes over the past two decades. Tax cuts and new spending initiatives coupled with multiple economic shocks have swelled budget deficits, Fitch said, while medium-term challenges related to rising entitlement costs remain largely unaddressed. Read more here.

China delivers 28nm lithography in 2023

By Global Times

China will launch its first 28-nanometer homegrown lithography machine at the year-end, leapfrogging US-led suppression and containment of its semiconductor sector. According to the Securities Daily, Shanghai Micro Electronics Equipment Group (SMEE) has been committed to developing a 28-nm immersion lithography machine, and it's expected the first domestically produced SSA/800-10W lithography machine will be delivered to the market by the end of 2023.

It will be a major breakthrough for the industry and homegrown chips are to be produced that meet the requirements of commonly used devices, Zhang Hong, a Beijing-based semiconductor industry analyst, told the Global Times on Tuesday.

Founded in 2002, SMEE is one of China's leading lithography machine makers and accounts for about 80 percent of the domestic market, industry sources said. Reuters described the company as China's only potential competitor to the Netherlands' world-leading lithography machine maker ASML.

SMEE's website noted that it has developed machines capable of manufacturing chips at the 90-nm node standard - a technology that is suitable for producing low-end chips. He Rongming, vice chairman of SMEE, led a team in five years of research and development, and the team achieved a major breakthrough in the crucial exposure process. The reported achievement comes at a critical time when the US has persuaded its allies, including Japan and the Netherlands, to join in its effort to contain China's tech sector growth, though it means considerable economic losses for companies in the two countries.

Japan announced in late March a draft revision to a ministry ordinance on its Foreign Exchange and Foreign Trade Act, adding 23 chip-manufacturing items that would require government approval to be exported. The rule took effect on July 23.

The Dutch government announced a ministerial order in early July to restrict exports of certain advanced semiconductor equipment. The export controls will come into effect on September 1.

To cope with the US-led suppression, Chinese companies are forced to make their own tools in a bid to avoid being squeezed by the US, an industry player told the Global Times on condition of anonymity on Tuesday. Moreover, as most companies are increasingly inclined to adopt domestic products, a virtuous cycle in the industry has been formed, according to the person.

For instance, an imported chip costs 20 yuan ($2.8), while the domestic replacement costs up to 200 yuan. Even the higher price doesn't deter Chinese companies which prefer using homegrown chips to mitigate market risks. As the demand for homegrown chips rises significantly, their prices will fall and their performances will improve over time, fostering a positive feedback loop.

The source said that key companies in the industry will lead the domestic substitution efforts, and offer technology support to their customers. "The progress of domestic substitution, which has been going on for about four years, went much faster than we anticipated," the person said.

On November 15, 2022, the National Intellectual Property Administration disclosed Huawei's ground-breaking new patent titled "Reflective Mirror, Lithography Apparatus, and Control Method", representing a significant advancement in the core technology of extreme ultraviolet (EUV) lithography machines.

The second phase of the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund Co, also known as the "Big Fund II," has invested heavily in China's semiconductor manufacturing, equipment and related materials and software development.

"But technology evolution needs years of consistent research and development, and we need to be patient and firm," Zhang Hong said. Zhang also pointed out that chip production is not something that one country can do all on its own, and China should seek cooperation with those who advocate for globalization.

The most advanced EUV lithography machine has more than 450,000 components, exceeding the number of parts in an F1 racing car by more than 20 times, according to the Securities Daily.

Even ASML which holds a dominant position in the world's EUV lithography machine manufacturing, makes only 15 percent of the total components. The rest must be sourced from the global supply chain.

Read more here.

U.S. and EU fear China’s Rush Into Legacy Chips

(Edited)

U.S. and European officials are growing increasingly concerned about China’s accelerated push into the production of older-generation semiconductors and are debating new strategies to contain the country’s expansion.

President Joe Biden implemented broad controls over China’s ability to secure the kind of advanced chips that power artificial-intelligence models and military applications. But Beijing responded by pouring billions into factories for the so-called legacy chips that haven’t been banned. Such chips are still essential throughout the global economy, critical components for everything from smartphones and electric vehicles to military hardware.

That’s sparked fresh fears about China’s potential influence and triggered talks of further reining in the Asian nation, according to people familiar with the matter, who asked not to be identified because the deliberations are private. The U.S. is determined to prevent chips from becoming a point of leverage for China, the people said.

Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo alluded to the problem during a panel discussion last week at the American Enterprise Institute. “The amount of money that China is pouring into subsidising what will be an excess capacity of mature chips and legacy chips — that’s a problem that we need to be thinking about and working with our allies to get ahead of,” she said. (see more in next article below)

The most advanced semiconductors are those produced using the thinnest etching technology, with 3-nanometers state of the art today. Legacy chips are typically considered those made with 28-nm equipment or above, technology introduced more than a decade ago.

Senior E.U. and U.S. officials are concerned about Beijing’s drive to dominate this market for both economic and security reasons, the people said. They worry Chinese companies could dump their legacy chips on global markets in the future, driving foreign rivals out of business like in the solar industry, they said.

Western companies may then become dependent on China for these semiconductors, the people said. Buying such critical tech components from China may create national security risks, especially if the silicon is needed in defense equipment.

“The United States and its partners should be on guard to mitigate nonmarket behaviour by China’s emerging semiconductor firms,” researchers Robert Daly and Matthew Turpin wrote in a recent essay for the Hoover Institution think tank at Stanford University. “Over time, it could create new U.S. or partner dependencies on China-based supply chains that do not exist today, impinging on U.S. strategic autonomy.”

The importance of legacy chips was highlighted by the impact of the Trump administration’s tech and trade war on China which caused the supply shocks that roiled companies at the height of the Covid pandemic, including Apple Inc. and carmakers. Chip shortages cost businesses hundreds of billions of dollars in lost sales. Simple components, such as power management circuits, are essential for products like smartphones and electric vehicles, as well as military gear like missiles and radar.

The U.S. and Europe are trying to build up their own domestic chip production to decrease reliance on Asia. Governments have set aside public money to support local factories, including the Biden administration’s $52 billion for the CHIPS and Science Act.

But domestic producers may be reluctant to invest in facilities that will have to compete with heavily subsidized Chinese plants. The Biden administration and its allies are gauging the willingness of Western companies to invest in such projects before they decide what action to take.

While the U.S. rules introduced last October slowed down China’s development of advanced chipmaking capabilities, they left largely untouched the country’s ability to use techniques older than 14-nanometers. That has led Chinese firms to construct new plants faster than anywhere else in the world. They are forecast to build 26 fabs through 2026 that use 200-millimeter and 300-mm wafers, according to the trade group SEMI. That compares with 16 fabs for the Americas.

Heavy investments have allowed Chinese companies to keep supplying the West, despite rising tensions between Washington and Beijing. China’s chipmaking champion, Semiconductor Manufacturing International Corp., got about 20% of last year’s sales from U.S.-based clients, including Qualcomm Inc., despite being blacklisted by the American government.

“When you think about electrification of mobility, think about the energy transition, the IoT in the industrial space, the roll-out of the telecommunication infrastructure, battery technology, that’s all — that’s the sweet spot of mid-critical and mature semiconductor,” Peter Wennink, chief executive officer of Dutch chipmaking equipment supplier ASML Holding NV, told analysts in mid-July. “And that’s where China without any exception is leading.”

Read more here.

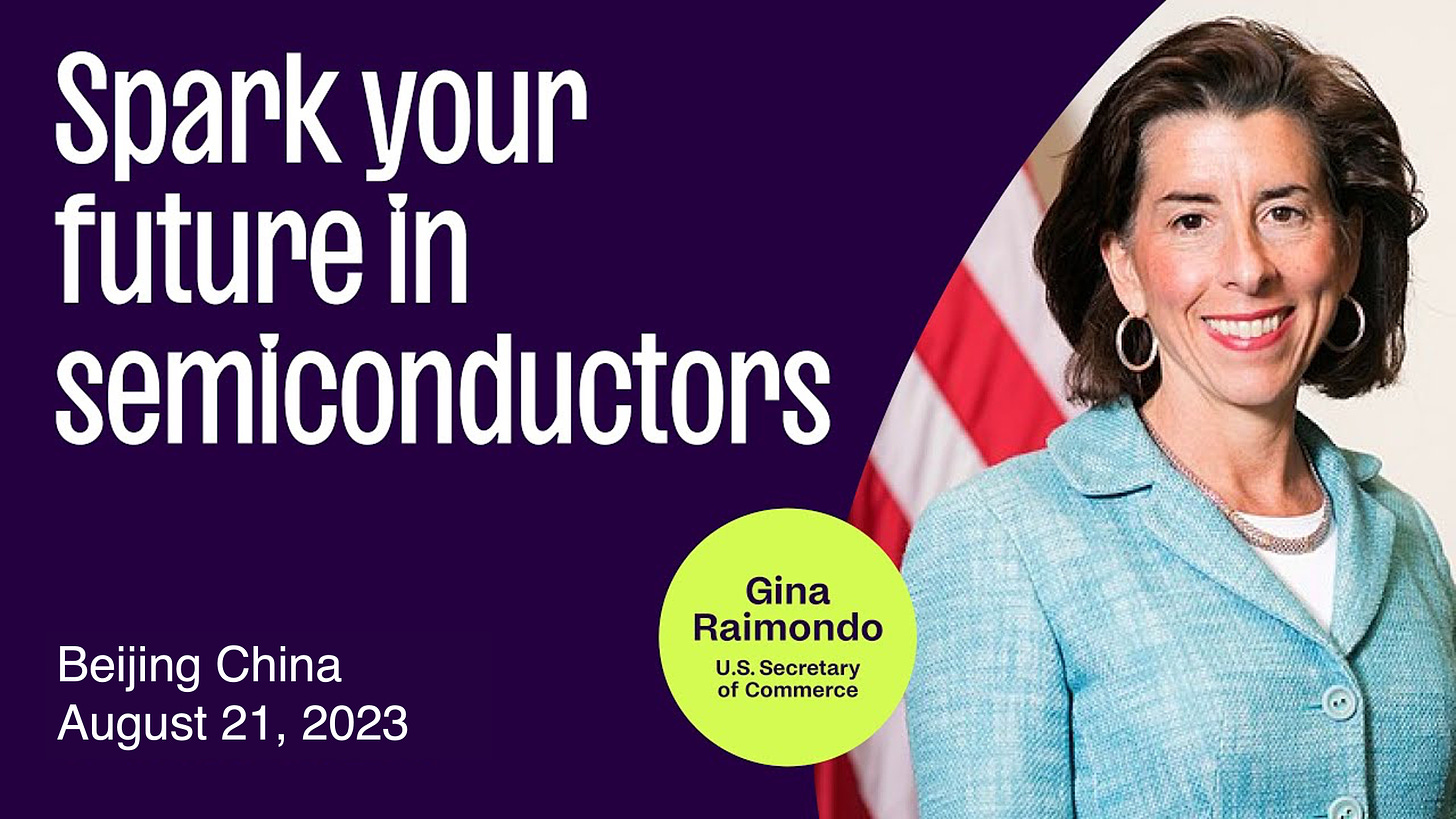

Gina Raimondo Plans China Chip Trip

By Bloomberg (edited)

US Commerce Secretary Gina Raimondo is planning to visit China in late August, according to people familiar with the matter, part of the Biden administration’s effort to undo its ill conceived semiconductor and tech war on China.

Raimondo is aiming to travel to Beijing the week of Aug. 21, although the dates aren’t finalized and could shift, according to the people, who spoke on condition of anonymity to discuss her plans.

It’s also still unclear what Raimondo could expect to deliver for US businesses, the people said, and the Commerce chief is hesitant to go without knowing that the trip will yield positive outcomes for American firms.

The Commerce Department’s press office declined to comment on trip timing and didn’t respond to questions about the topics Raimondo would want to discuss with her counterparts. She said at an event in Washington last week that she plans to go to China “later this summer” but is “still finalizing a date and plans.”

Raimondo, whose emails were hacked earlier this month in a breach tied to China, has been at the forefront of White House efforts to curb Beijing’s access to advanced technology, including export controls announced last year.

Her trip could come at a sensitive time in the bilateral relationship, with Biden set to sign an order curbing critical US technology investments in China by mid-August.

On her first trip to China as commerce secretary, Raimondo would be the fourth high-level member of President Joe Biden’s administration to visit since June, following Secretary of State Antony Blinken, Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen and climate envoy John Kerry.

The earlier visits by top administration officials have yet to deliver significant public results beyond agreeing to further dialogue. The White House is looking to smooth ties with Beijing following months of heightened tensions over incidents including an alleged spy balloon, the US export controls on computer chip technology and military encounters in the South China Sea.

Read more here.

US 28nm Legacy Chip Anxiety

By Sujai Shivakumar (edited)

The US chip shortage was largely the outcome of the Trump administrations launch of a Tech and Trade war against China before the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. The pandemic drew widespread attention to the fact that the most advanced semiconductors are no longer manufactured in the United States, and that this represents a strategic vulnerability. The shortfall adversely affected not only traditional industries like automobiles but also other devices that incorporate a complement of semiconductor technologies—including microprocessors, advanced microcontrollers, analog and mixed-signal products, and power semiconductors—and drive displays, decode audio, operate engines, and perform other key functions. The absence of these components created significant disruptions in the U.S. economy, prompting a deeper look at the strategic significance of so-called legacy chips.

“Legacy” or “mainstream” semiconductor-based integrated circuits (ICs) are made using established—but still evolving—manufacturing processes, typically with larger transistors etched on each chip. The CHIPS and Science Act of 2022 defines legacy devices as those produced with 28-nanometer (nm) technology or larger, and it tasks the Department of Commerce with formulating a precise definition for other types of chips. That determination is still pending. The official definition of “cutting-edge” chips has also yet to be formulated but can be assumed to apply to process nodes at or below 5 nm. The highly advanced 10 nm and 7 nm chips are in a definitional gray area, at least until the Department of Commerce categorizes them. Even then, this is a static distinction in a technology that is still following a trajectory predicted by Moore’s Law: what is considered “legacy” today was cutting-edge not long ago, and what is cutting-edge today is destined to become tomorrow’s legacy chip.

Legacy chips are ubiquitous. While cutting-edge chips or microprocessors have widespread applications in critical technologies, legacy chips are involved in the production of most automobiles, aircraft, home appliances, broadband, consumer electronics, factory automation systems, military systems, and medical devices. These devices have a central role in the U.S. manufacturing economy, meaning disruptions in the availability of legacy chips negatively impact U.S. manufacturing and downstream economic activities.

Despite the name, legacy chips are not stale technology, because these categories of chips are constantly being refined for new requirements and applications. Innovations in these chips, for example, include the use of silicon carbide semiconductors, which are expected to have an important role in decarbonizing the economy. Legacy chips are destined to remain highly relevant to emerging industries and technologies far into the future.

A 2021 Biden administration review of the U.S. semiconductor supply chain found that “the United States relies on sources concentrated in Taiwan, South Korea, and China to meet demand for various non-leading-edge memory and logic chips that are used widely in myriad consumer and industrial applications.” In 2022, the Department of Commerce concluded—based on a survey of over 150 U.S. companies that produce and consume semiconductors—that a chip shortage was “threatening American factory production and helping to fuel inflation.” Secretary of Commerce Gina Raimondo said on January 25, 2022, that “it’s alarming, really, the situation we’re in as a country, and how urgently we need to move to increase our domestic capacity.”

Considering semiconductors take many months to manufacture—with typical automotive microcontrollers taking six to nine months—current supplies reflect 2022 boosts in production volume, and the market now faces an oversupply for certain kinds of chips. However, the auto industry still faces a shortage of semiconductors.

Auto sector underinvestment has been particularly acute with respect to analog devices, which process information along gradients rather than just according to on and off signals. STMicroelectronics NV, one of the world’s largest makers of analog chips, forecasts that its backlog of automotive orders will “continue to exceed existing and anticipated manufacturing capacity through 2023.”

More generally, the U.S. chip industry is losing the capability to produce some types of legacy devices altogether. This is not a reflection of technical hurdles but rather of the fact that older fabs are closing down and not being replaced given the associated difficulties.

Supply constraints have disrupted medical device producers, and makers of electronic consumer products. In 2021, Apple was forced to curtail its production plans for iPhones and other devices because of shortages. With respect to the iPhone 13 Pro Max, a highly complex device incorporating over 2,000 components, the shortfall did not occur with respect to the most advanced chips. Instead, shortages in peripheral components costing just a few cents—such as power management chips made by Texas Instruments, transceivers from Nexperia, and connectivity devices from Broadcom—held up production. Importantly, “such chips are not unique to the iPhone, to smartphones, or even to consumer electronics, but are used across computers, data centers, home appliances, and connected cars.”

An unintended consequence of U.S. export controls on advanced chip technology to China may be a wave of state-backed investment leading to overproduction and, potentially, Chinese dominance of global legacy chip production. Maintaining a robust and resilient supply base able to make the investments and to produce and improve constantly higher node chips is essential for each nation’s competitiveness and economic security. Moreover, innovation in the higher-node chips is expected to serve as the foundation for a variety of emerging technologies, including those necessary to power a greener, healthier planet. More advanced, higher-node chips will be needed to produce green energy technologies, a domain that neither China, Europe or the United States can afford to ignore.

Read more here.

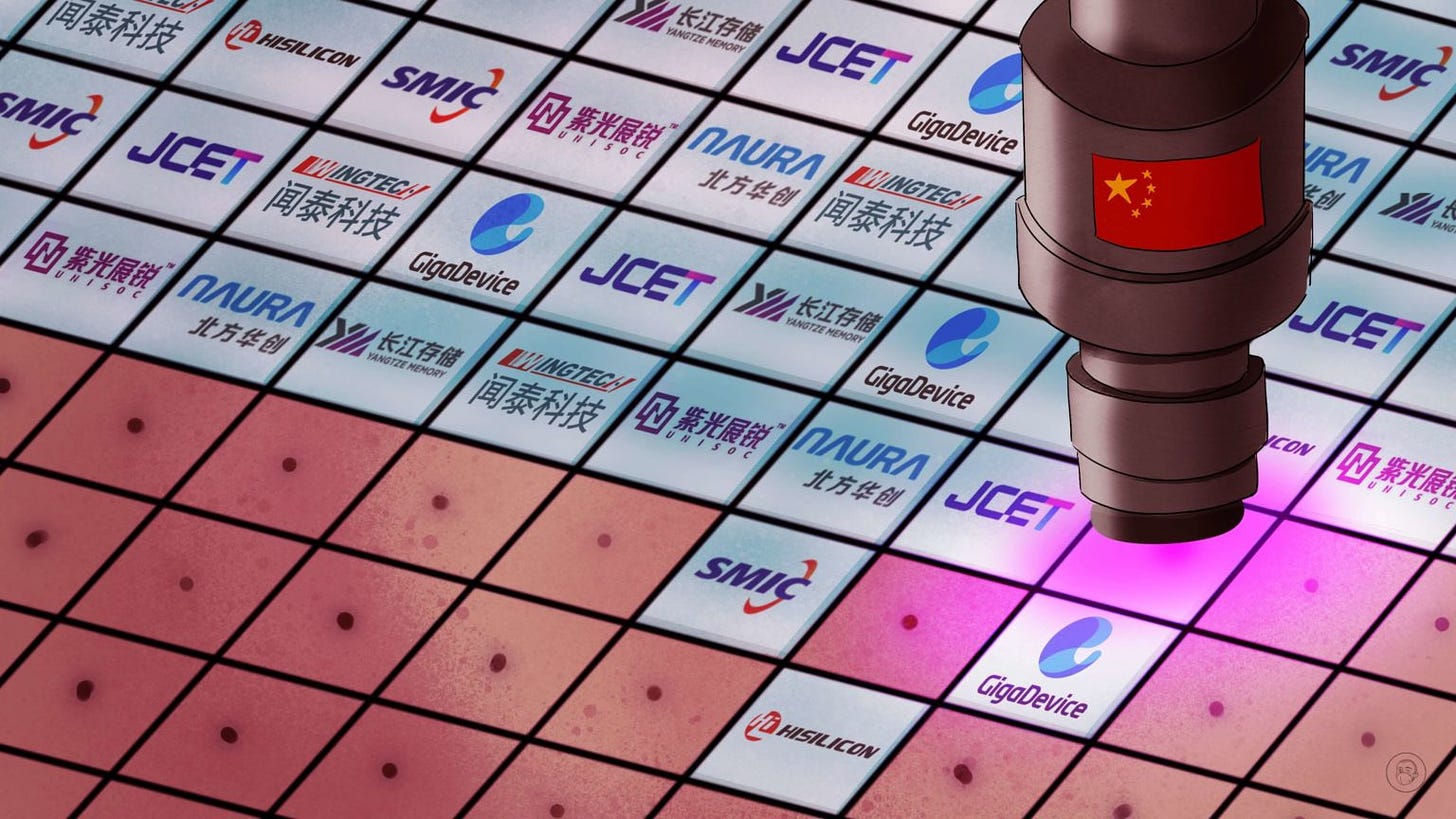

China’s top 10 semiconductor firms

By Arran Hope (edited)

China’s chip industry has been juiced by funding from the government and jinxed by U.S. export curbs on advanced equipment. But the century of chip rivalry has just started. These are ten Chinese semiconductor firms to look out for and three that went down in flames.

The global semiconductor industry is valued at over half a trillion U.S. dollars, and its products — the microchips used in everything from cars to phones to ballistic missiles, affect every single person on the planet. Making chips is a highly complicated business that involves world-wide supply chains.

Advanced chip design is dominated by American firms. The chips themselves are mostly manufactured in Taiwan, China, and Malaysia, but this can only happen with equipment and chemicals sourced from Europe, Japan, and North America. An example of the complexities involved: To fabricate a wafer — a thin slice of semiconductor material on which an integrated circuit is printed to make a chip — requires over one thousand individual steps, four hundred or so different chemicals, and up to 50 separate types of equipment.

In China alone, there are tens of thousands of semiconductor companies. The country is also the largest consumer of semiconductors in the world: in 2020, China bought 53.7% of the world supply of chips worth around $240 billion. However, this is yet to translate into Chinese domination of the industry as a whole — far from it. Although China makes plenty of lower-end chips, it remains dependent on foreign suppliers and foreign-owned technologies for the advanced semiconductors needed for phones, smart cars, artificial intelligence, and military applications.

Beijing wants China to to become a key player in the global industry, and to end its reliance on foreign companies. To this end, it established the National Integrated Circuit Industry Investment Fund 国家集成电路产业投资基金, also known as the “Big Fund” (大基金) in 2014 which has a a minority shareholding in 74 companies and has invested in 2,793 entities, the majority of which are semiconductor firms.

According to the Semiconductor Industry Association’s State of the Industry Report, published in November 2022, China’s share of the global chip design market is projected to rise from 9% in 2020 to 23% by 2030 (compared to a U.S. decline from 46% to 36%) — a substantial increase, but still far from world-beating.

While yet to be competitive in the design and production of leading edge chips, China does have an advantage relative to the U.S. in packaging and testing (known in industry jargon as outsourced semiconductor assembly and testing or OSAT), where in 2021 it accounted for 38% of the global market.

However, as the U.S. continues its campaign to curb sales of advanced technologies to China, the country’s chances of catching up look slim.

In 2023, China’s semiconductor industry is entering some of the toughest operating conditions it has ever had to face. On the one hand, the internationally-coordinated imposition of export controls, spearheaded by the U.S., has left many firms in the difficult position of being unable to acquire a lot of the technology they need to advance their businesses. HiSilicon has had something of a head start on this front, having faced export restrictions for over two years now. But even so, Chinese officials are now having to completely rethink how Chinese companies will be able to develop core technologies.

Internally too, there are problems: The spigots from Beijing are running dry, as suggested by recent signals that a huge investment plan for the industry is being overhauled. While the previous model led to the kinds of excesses of HSMC and others, the industry is nevertheless enormously capital intensive. But with the priority on returning the Chinese economy to robust growth this year, such profligacy on projects that won’t see returns for years to come will be hard to maintain.

Some firms will fold, others will focus on churning out less advanced chips, and the sector as a whole will keep striving for self-reliance. The other response we are likely to see is a retaliatory action from the Chinese government against U.S. restrictions. What form this will take remains to be seen. But for now the chips are very much down, and Beijing does not have the strongest hand.

Follow the link below for an introduction to ten key Chinese firms that cover various aspects of the industry.

Read more here.