Flag Follows Trade

Floating Fukushima?, Belt and Road Still Going Strong?, Australia Eyes ANZUS Exit

Floating Fukushima

The HEAT (CGTN Television)

Panel Discussion on new developments with AUKUS and what it means for the Pacific region with Josef Gregory Mahoney (Professor of Politics and International Relations, East China Normal University Shanghai).

The US is leveraging its position as the world-leading economy, world-leading oil producer, world-leading food exporter, and world-leading defence industry. It has the most powerful military, it controls the value of the currency used in most global trade, and has almost unilateral control over the global financial system.

Since the end of the WWII there is a clear, consistent pattern of the US using such powers imperialistically to ensure it remains at the top internationally. One can well argue that this trend had earlier beginnings, when the US began to move decisively in the 19th century to establish itself as regional hegemon and its gradual emergence as a major power. This trend did not end with thecollapse of the #ussr

The world today is on the cusp of a new technological revolution, new crises associated with climate change, instability and polarisation in many if not all of the G7 countries, proxy wars in Ukraine and Gaza, and China's emergence as a major power.

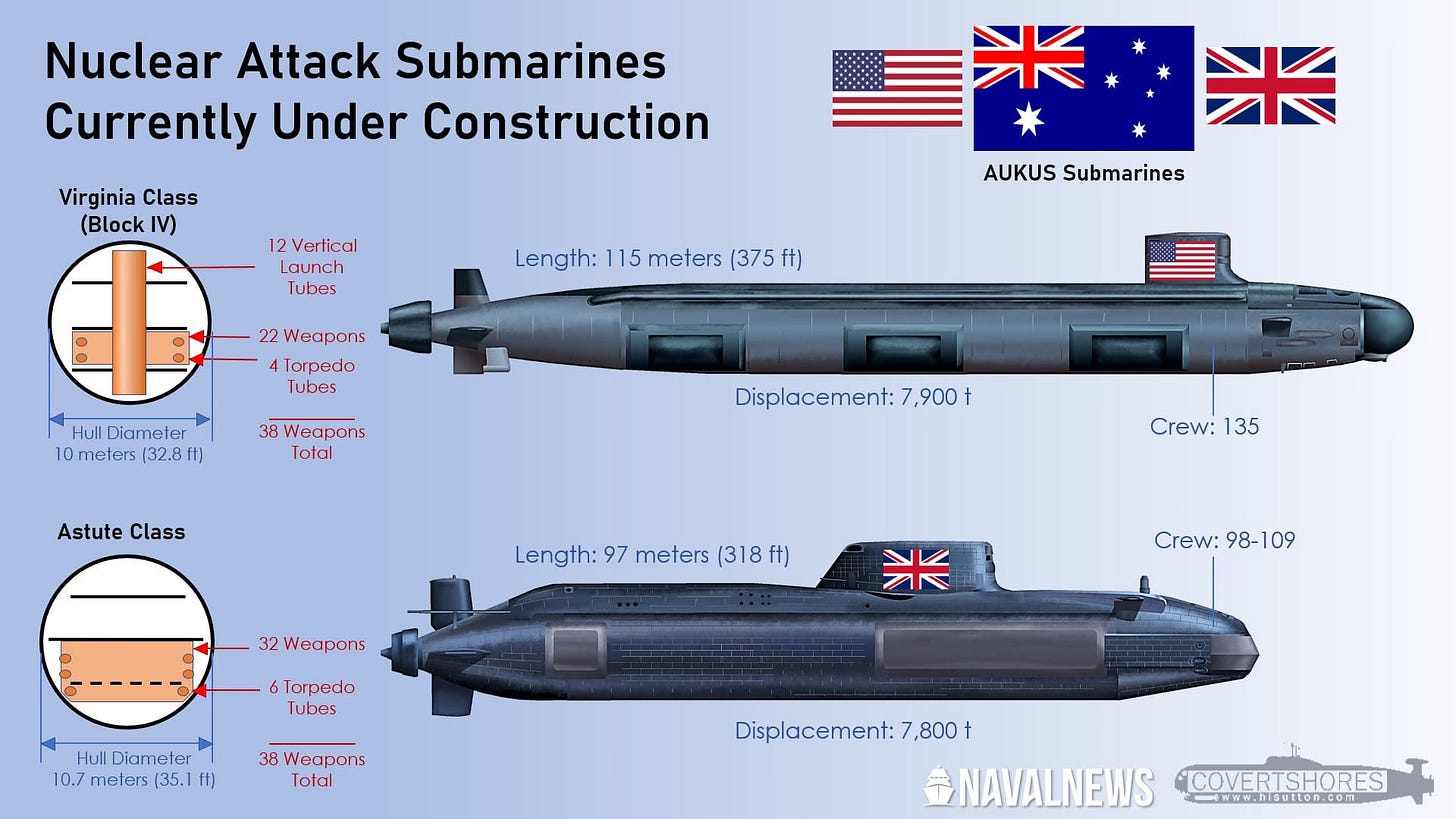

AUKUS is not yet a military alliance but appears to be the foundation for one that will be based on the Five Eves plus Japan and South Korea. Much has been made about nuclear proliferation ,about the US selling nuclear submarines to Australia capable of firing nuclear weapons and expanding airbases in northern Australia to host US bombers capable of carrying nuclear weapons. This signals the end of Australia's commitment to a nuclear-free South Pacific. It also saddles Australia with massive costs, meanwhile eroding sovereignty destabilising, war-oriented US security paradigm in so much as it's not just about dependence, but also whether Australia will actually command its own forces, including the submarines its buying (reports indicate Canberra will not control the sub). This is less about partnerships and more about customers who occupy a subaltern status.

The tech revolutions the driver here. It’s not simply that Australia’s diesel powered subs were obsolete, it's that increasingly American products integrate advanced AI, chipsets and information capabilities. Access to this tech requires joining the whole ecosystem. This is why Australia abandoned French replacement subs for American models.

The spectre of Washington controlling Australia's subs is but one ghost, the other is Al itself. Who controls it? Can it be hacked? Reprogrammed? Become self-aware? Accelerate conditions that spiral out of control? Do these risks increase as more countries join or cooperate, each with different cyber-defence capabilities and security clearance protocols.

Or perhaps Al is better than the American captain who wrecked his nuclear sub on a South China Sea seamount, endangering the entire region? lmagine each of these ships as a mobile Fukushima, all with immediate release into the sea.

Watch here.

Belt and Road Still Going Strong?

By Lim Guanie (Assistant Professor, National Graduate Institute for Policy Studies, Japan)

The reality is that very few economies have matched Chinese business groups’ appetite in pushing infrastructure projects, especially capital- and technology-intensive ones which take a long time to produce returns.

Relations between great powers and their neighbouring regions are often fraught. The cases of the United States and Latin America, or the European Union and North Africa, come to mind. For instance, tensions related to immigration from Latin America and North Africa, has led to the rise of right wing populism in the United States and Europe, respectively. This has fueled the rise of populist politicians such as Donald Trump in the United States and Marine Le Pen in France.

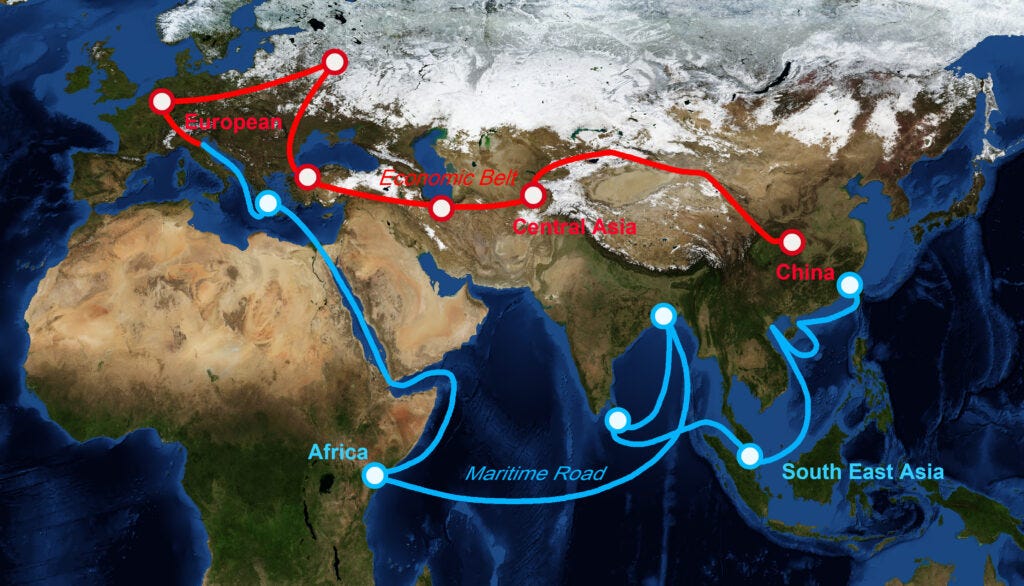

In China’s case, economic engagement has helped to stabilise and strengthen its relationship with Southeast Asian countries, despite ongoing disputes in the South China Sea. One important facet of this engagement is the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), which China launched 11 years ago.

Most of the Southeast Asian countries do not have the means to fund major infrastructure projects, resulting in an infrastructure deficit in the region. Chinese investments, including those of the BRI, have thus become an important economic force in Southeast Asia. The reality is that very few economies have matched Chinese business groups’ appetite in pushing infrastructure projects, especially capital- and technology-intensive ones which take a long time to produce returns. While other players have attempted to promote infrastructure building and other forms of cooperation in Southeast Asia, such as the EU’s Global Gateway, there is considerable room for improvement. By contrast, Chinese firms have managed to deliver some of the most challenging projects in the region. Two recent examples come to mind: the Boten-Vientiane railway in Laos and the Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail in Indonesia. The generally positive reception to these projects since their opening has likely increased the appeal of similar initiatives to the public.

Indonesia’s experience in opting for China (over Japan) for its landmark railway project is worth discussing. The Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail was one of the most heavily criticized Chinese projects before and during its construction. Despite some delays and dissenting voices along the way, the project began commercial operations in late 2023. Indonesian President Joko Widodo (Jokowi) and Coordinating Minister for Maritime Affairs and Investment Luhut Pandjaitan are evidently satisfied enough with the project’s outcome to want to continue cooperating with the state-owned China Railway Group Limited (CREC) to extend the railway service to Surabaya, Indonesia’s second-biggest city. The Jakarta-Bandung High Speed Rail has allowed Indonesian policymakers to address longstanding issues, such as the challenging task of setting up development links between Jakarta and smaller urban hubs. And, importantly, working on this project has enhanced the organizational capabilities of the Indonesian central and local governments, which will help them manage other complex undertakings in the future.

In Vietnam, ties with China have generally been cordial. Notwithstanding reservations in some quarters over the economic domination of China, the reality is a lot more nuanced. For one, Vietnam has harnessed the investment dollars of transnational corporations de-risking from China, transforming itself into a ‘connector economy’interlinking the US and Chinese markets. There is another subtext here – the influx of investment and businesses triggered by the US-China competition adds positive momentum to Vietnam’s attempts to continue and even deepen the pro-market reforms it first initiated in 1986. Vietnam and China are currently in the midst of exploring strengthening rail and road infrastructure and connectivity between the Yunnan province in China and Vietnam (including Hanoi and the port city of Haiphong), through the BRI initiative.

It is true that some of China’s ‘Going Out’ efforts have fallen short of their initial aims. Reasons for this range from political pushback in certain host economies to overoptimistic financial projections. This has led to adjustments, resulting in a shift towards “smaller, greener, and more beautiful” undertakings and projects centered on knowledge and technology, rather than resource- and labor-intensive endeavors. In addition, ad-hoc deals are transitioning towards more institutionalized arrangements, especially after the China International Development Cooperation Agency (CIDCA) was established in 2018. The CIDCA represents an institutional innovation to harmonize efforts across multiple state organs, with the overarching goal of implementing and overseeing development aid projects more effectively. These transitions, while not usually mentioned in the popular media, underline an important reality of economic cooperation: real and consequential changes often happen slowly and subtly, hidden far in the background.

It is reasonable to expect some occasional pit-stops as the BRI heads into its second decade in Southeast Asia. The key lies in exploring common platforms to further Southeast Asia-China cooperation. At the same time, it is important to avoid sweeping, oversimplified caricatures of Chinese capital exports. A more balanced perspective, which takes account of context-specific issues in the host economies and the region’s wider economic architecture, would be more fruitful.

Great powers and their neighbors share a common interest in fostering regional peace, prosperity, and political and economic stability. China has been instrumental in meeting the pressing need in Southeast Asia for infrastructure development through the BRI, and it has in turn reaped political and economic dividends. Economic interdependence has also raised the costs of potential regional conflict. The role of the BRI in managing the China-Southeast Asia relationship could serve as a valuable model for study for other great power-neighborhood relations, such as those between the United States and Latin America and between the European Union and North Africa.

Read more here.

Australia Eyes ANZUS Exit

By Mike Scrafton (Pearls and Irritations)

How long can Australian politicians continue with the pretence that the American alliance aligns with the nation’s interests? Trump or Biden? It doesn’t really matter except for determining the path of America’s decline into illiberalism. ANZUS must be exited.

There are three compelling arguments for leaving the ANZUS alliance.

The first is cynical but persuasive; America’s influence and therefore its ability to provide for Australia’s security is lessening rapidly. A string of foreign policy failures alongside the rise of significant regional powers like China, India, and Indonesia, and the loss of credibility and moral standing both inside and outside Europe and North America because of Ukraine and Gaza, have ensured this.

Then there is the potential dissolution of the Republic as the domestic anti-democratic, illiberal, and authoritarian forces surge bringing ever-increasing division, political violence, and dysfunction. Whichever way the presidential election goes these trends will intensify, and the growing disregard for the constitutional constraints on the use of state-sponsored violence against civil society, and the general tolerance and proclivity for political violence, hover over everything.

In a recent interview Donald Trump told Time Magazine that if local police and the National Guard couldn’t handle the round-up and expulsion of illegal immigrants, he “would have no problem using the military”. To facilitate local implementation of the round-up of illegal immigrants he plans “to give police immunity from prosecution”. Asked if he would pardon all January 6 offenders if elected he answered “yes” (Read here). Political violence not simply tolerated but facilitated.

Biden’s attitude to the police actions against students confirms that political violence is endemic in America irrespective of who is in power. This violence is a pathological symptom of continued decline into illiberalism and authoritarianism. Biden’s statements accord no weight to the student protesters’ legitimate dismay at American support for war crimes and for potential genocide of Palestinians in Gaza.

The President’s law-and-order justification of police brutality can been seen simply as camouflage for suppression of dissent. Were images similar to those of police in riot-gear assaulting unarmed protesting students on American university campuses to come out of Hong Kong, Teheran, or Moscow, they would have been condemned as violent suppression of the students’ civil rights. The hypocrisy is clear.

The most important reason, however, is the deleterious impact the alliance is having on politics and society in Australia. The government might deny that AUKUS infringes on Australia’s sovereignty, and especially on its capacity for making the war decision, but the facts speak for themselves.

Two things are irrefutable. Australia has become a rear-area resupply base for American forces operating into the South China Sea; a situation that will become more embedded as the armaments industry in Australia develops along the lines set out in the National Defence Strategy (NDS). What the NDS promotes as National Defence is simply the militarisation of a significant sector of Australia’s economy, under the AUKUS arrangements, to supply, maintain, and facilitate US forces.

Also, it can only be the case, as is strongly implied in the NDS, that Australia has now outsourced its defence to the US for at least the next two decades. This circumstance puts Australian governments in an unavoidable submissive position in relation to American interests. The lauded ‘enhanced lethality’, ‘impactful projection’, and conventionally armed nuclear-powered submarines will emerge, if ever, only in the second half of the century, leaving Australia reliant on decrepit platforms and the kindness of America.

Both of these facts tie Australia unbreakably into the American decline. Already as a consequence of the AUKUS arrangements Australia will not be able to field any semblance of a viable defence force until the late 2030s – early 2040s at best. To fit in with America’s force positioning in the Asia-Pacific, Australia has become the supplicant vassal in the ANZUS alliance.

It has been observed that extracting Australia from the alliance would be an inordinately difficult task, and one that it seems very unlikely that any government would attempt to do on its own initiative; currently it would be electoral suicide. Public opinion in Australia generally favours the alliance, although probably in an inattentive and unreflective way. The Washington-drafted talking points on the China threat, and on the centrality of US hegemony to… well, everything, are dutifully repeated by Australian politicians, fed to think-tanks, and echoed by the mainstream media without much scrutiny or critique.

However, anecdotally it seems that much of the serious analysis by academics, and retired professionals, and independent experts, is awake to the dangers posed to Australia by America’s foreign policy and its influence over Australia defence, security, and intelligence thinking; not to mention the danger from America’s steep descent from the democratic and liberal principles it purports to maintain at home and pursue internationally. Over time this insidious influence has suborned Australia’s policies and Americanised thinking in Canberra.

The impetus to escape from ANZUS will have to come from the voters. New political voices will need to be heard and to persuade the electorate of the loss of Australia’s sovereignty and of the potential disaster that will come from having no other choice but to follow a fading, corrupted, and illiberal America into a pointless and disastrous war with a nuclear-armed nation. This is a message that can be explained clearly and unambiguously if accorded the exposure by the media.

It is imperative for Australians, now and for decades hence, that the ANZUS links be broken. Australia has a great many more urgent priorities for scarce funding – mitigation and adaptation to climate change, health, infrastructure, education, food security, etc – rather than allocating obscene amounts of national treasure to bolstering the American war machine under the auspices of ANZUS.

Read more here.